By Dr. Jerry Shurson, University of Minnesota Department of Animal Science and Dr. Brian Kerr, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s National Laboratory for Agriculture & the Environment in Ames, Iowa

© 2019 Feedstuffs. Reprinted with permission from Vol. 91, No. 01, January 14, 2019More than 90% of fuel ethanol plants in the U.S. are separating corn oil from thin stillage to produce distillers corn oil (DCO).

In 2017, the U.S. ethanol industry produced about 3.6 billion lb. of DCO, with about half of this total being used to produce biodiesel and the other half marketed as a high-quality energy source for use in poultry and swine diets.

The abundant supply of DCO, its high metabolizable energy (ME) content and relatively low price compared with other feed fats and oils make it an attractive energy source to use in commercial swine diets. The market price of DCO is closely related to the price of yellow grease in the U.S. market for fats and oils, but DCO has a substantially greater ME content than yellow grease, and while the ME content is comparable to soybean oil, soybean oil is more expensive.

Some U.S. poultry and pork market segments have chosen to produce chicken and pork by feeding only “vegetable-based” diets (which include vegetable oils) to meet specific consumer demands as part of their marketing strategies. Furthermore, the perceived risk of pathogenic virus transmission from adding porcine-derived feed ingredients to swine diets in the U.S. has led some veterinarians and nutritionists to remove these ingredients (e.g., choice white grease, animal byproduct protein meals) and replace them with only plant-based ingredients such as corn, soybean meal, dried distillers grains plus solubles (DDGS) and DCO.

Up until recently, the use of DCO in swine diets has generally been limited to the nursery and early grower phases, because feeding high concentrations of corn oil reduces the firmness of pork fat. A reduction in carcass fat firmness can reduce bacon yield, may shorten the shelf life of fresh pork products and can negatively affect pork quality acceptability in the Japanese export market.

However, now that an approved “generally recognized as safe” commercial feed additive is available (from NutriQuest) that’s effective in preventing reductions in pork fat firmness when feeding growing/finishing diets containing high amounts of unsaturated fatty acids from vegetable oils (i.e., DDGS and DCO), concerns about high dietary inclusion rates of DDGS and DCO are minimal.

In 2016, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (2017) developed and approved the official definition for DCO for use in animal feeds as follows: “33.10 Distillers Oil, Feed Grade, is obtained after the removal of ethyl alcohol by distillation from the yeast fermentation of a grain or a grain mixture and mechanical or solvent extraction of oil by methods employed in the ethanol production industry. It consists predominantly of glyceride esters of fatty acids and contains no additions of free fatty acids or other materials from fats. It must contain, and be guaranteed for, not less than 85% total fatty acids, not more than 2.5% unsaponifiable matter and not more than 1% insoluble impurities. Maximum free fatty acids and moisture must be guaranteed. If an antioxidant(s) is used, the common or usual name must be indicated, followed by the words ‘used as a preservative.’ If the product bears a name descriptive of its kind of origin, e.g., ‘corn, sorghum, barley, rye,’ it must correspond there to with the predominating grain declared as the first word in the name.” (Proposed 2015; adopted 2016, rev. 1.)

DCO chemical composition

One of the distinguishing features of DCO compared with refined corn oil is that many DCO sources have greater free fatty acid (FFA) content (Table 1), which can range from less than 2% to as much as 18%. Previous studies evaluating various feed lipids have shown that increasing FFA content reduced ME content for pigs and poultry and, as a result, led to the development of digestible energy (DE) for swine and nitrogen-corrected apparent ME for poultry prediction equations (Wiseman et al., 1998).As a result, DCO contains one of highest ME concentrations of all feed fats and oils in the market, but it is also more susceptible to oxidation during thermal processing and storage (Kerr et al., 2015; Shurson et al., 2015; Hanson et al., 2015). Feeding oxidized lipids to pigs and broilers has been shown to reduce growth rate, feed intake and gain efficiency (Hung et al., 2017), and highly oxidized corn oil reduces the efficiency of energy utilization and antioxidant status in nursery pigs (Hanson et al., 2016).

However, the addition of commercially available antioxidants to DCO has been shown to be effective in minimizing oxidation of DCO when stored at high temperature and humidity conditions (Han- son et al., 2015). Although the extent of oxidation (peroxide value, anisidine value and hexanal) in DCO is somewhat greater than in refined corn oil, it is much less than in the oxidized corn oil fed to nursery pigs in the study by Hanson et al. (2016), where reductions in growth performance were observed.

A comparison of the chemical composition and oxidation indicators of two commercially available DCO sources with choice white grease, refined palm oil and soybean oil is shown in Table 2. Choice white grease (rendered pork fat) consists primarily of oleic acid (9c-18:1), palmitic acid (16:0) and stearic acid (18:0), which results in this lipid source being classified as a saturated fat source compared with DCO.

In general, saturated animal fats (e.g., choice white grease) have less ME content than more unsaturated vegetable oil sources (e.g., DCO). Because choice white grease contains a greater proportion of saturated fatty acids than DCO, it is less susceptible to lipid oxidation than DCO, but the temperature and heating time used during rendering can result in a similar amount of peroxidation compared with DCO (Table 2).

The predominant fatty acids in refined palm oil are palmitic (16:0) and oleic (9c- 18:1) acid, and the linoleic acid content (9.85%) is much less than what’s found in DCO (56%). As a result, palm oil is much more resistant to oxidation, as indicated by a high oil stability index (OSI), compared with DCO, choice white grease and refined soybean oil (Table 2).

In contrast, the fatty acid profile of refined soybean oil was similar to that of DCO and contained high concentrations of linoleic acid (53%), with moderate concentrations of oleic (23%) and palmitic (11%) acids. However, unlike DCO, soybean oil contains relatively high concentrations of linoleic acid (18:3n-3), which makes it more susceptible to oxidation than DCO. Because the soybean oil source evaluated in this study was refined compared with feed-grade sources, it contained a lower concentration of aldehydes (products of oxidation), as measured by anisidine value and 2,4 decadienal, compared with DCO, choice white grease and palm oil.

Compared with choice white grease and refined palm oil, DCO contained relatively high concentrations of total tocopherols (626-730 mg/kg) and xanthophylls (92-175 mg/kg). Only soybean oil had greater total tocopherol content than DCO, but soybean oil is essentially devoid of xanthophylls. Tocopherols and carotenoids (xanthophylls) are strong antioxidant compounds that may be beneficial in reducing oxidative stress in nursery pigs fed diets containing highly oxidized DDGS (Song et al., 2013). Therefore, the high tocopherol and xanthophylls content of DCO may be a “value-added” feature and incentive for its use in swine diets to reduce oxidative stress, but more research is needed to explore this potential benefit.

Actual vs. predicted DE, ME

Two studies have been conducted to determine the DE and ME contents of DCO for swine.The first study was conducted by Kerr et al. (2016) to determine the DE and ME content of refined corn oil (0.04% FFA), three sources of commercially produced DCO with FFA content ranging from 4.9% to 13.9% and an artificially produced high-FFA (93.8%) corn oil source. In addition, the effect of FFA content on the ME content of DCO sources was evaluated.

As shown in Table 3, the ME content of DCO samples ranged from 8,036 to 8,828 kcal/kg, with the 4.9% FFA DCO sample containing similar ME content to refined corn oil. The ME values for refined corn oil (8,741 kcal/kg), 4.9% FFA DCO (8,691 kcal/kg) and 13.9% FFA DCO (8,397 kcal/ kg) were similar to the value for corn oil (8,570 kcal/kg) reported in the 2012 National Research Council (NRC).

The accuracy of using prediction equations developed by Wisemann et al. (1998) to predict the DE content of DCO sources was also evaluated to determine if these prediction equations are applicable to DCO sources to provide more dynamic and accurate DE estimates based on variable FFA composition of DCO sources (Table 3).

The Wiseman et al. equations use FFA content, unsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio and age of pig as the inputs to estimate DE content. Unfortunately, the results from using these equations showed that DE content was overestimated in refined corn oil and the 12.8% and 13.9% FFA DCO sources but provided a similar estimate of DE content for the 4.9% FFA DCO source and greatly underestimated (1,146 kcal/kg) the DE content of the experimentally produced high FFA DCO source.

These results suggest that the Wiseman et al. (1998) prediction equations need to be reassessed to improve the accuracy and precision of predicting fats and oils not used in their development, such as for DCO.

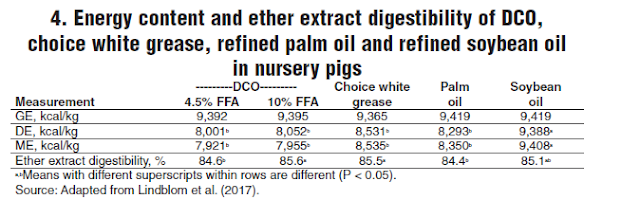

In a subsequent study, Lindblom et al. (2017) determined the DE and ME content of two different DCO sources – 4.5% and 10% FFA – and compared these values with commercially available sources of choice white grease, palm oil and soybean oil (Table 4).

The ME values obtained for both DCO samples were substantially less (7,921 and 7,955 kcal/kg) than the values obtained for two of the three DCO sources (8,397 to 8,691 kcal/kg) previously evaluated by Kerr et al. (2016). It is unclear why there was a difference in the ME content of DCO sources between these two studies, but these results provide further support that the FFA content of DCO does not appear to affect the ME content for swine.

It was also surprising that the ME content for choice white grease (8,535 kcal/kg) was greater than for both DCO samples in the Lindblom et al. (2017) study and was also greater than the NRC (2012) value of 8,124 kcal/kg, because it is well documented (NRC, 2012) that unsaturated lipid sources have historically had greater lipid content than saturated fat sources.

However, it is possible that the widespread use of high dietary inclusion rates of DDGS in U.S. growing/finishing pig diets may have resulted in a shift toward more unsaturated fatty acid content in choice white grease obtained from the carcasses of these pigs. Evidence for this is supported by the greater linoleic acid content (16%) of this source of choice white grease compared with the NRC-reported level (11.6%).

Furthermore, there was a slight decrease in palmitic acid in this source of choice white grease compared with the NRC level, at 23% versus 26%, respectively. In addition, the ME content of the soybean oil source evaluated by Lindblom et al. (2017) was substantially greater than the value reported by NRC, at 9,408 kcal/kg versus 8,574 kcal/kg, respectively.

These results show the potential risks of overestimating or underestimating the ME content of feed fats and oils when using static values from reference databases.

Conclusion

DCO is produced in abundant quantities by the U.S. ethanol industry and is competitively priced but has variable ME content among sources that does not appear to be associated with its FFA content. New prediction equations need to be developed, or existing equations need to be modified, to more accurately estimate the DE and ME content of DCO for swine, because using previously developed equations results in a significant overestimation of actual DE content.The relatively high concentrations of tocopherols and xanthophylls may also provide significant antioxidant value when DCO is added as a supplemental energy source to swine diets, but more research is needed to determine if these potential benefits are achieved under commercial production conditions.

References

Association of American Feed Control Officials. 2017. Official Publication. Champaign, Ill.Hanson, A.R., P.E. Urriola, L.J. Johnston and G.C. Shurson. 2015. Impact of synthetic antioxidants on lipid peroxidation of distiller’s dried grains with solubles and distiller’s corn oil under high temperature and humidity conditions. J. Anim. Sci. 93:4070-4078.

Hanson, A.R., P.E. Urriola, L. Wang, L.J. Johnston, C. Chen and G.C. Shurson. 2016. Dietary peroxidized maize oil affects the growth performance and antioxidant status of nursery pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 216:251-261.

Hung, Y.T., A.R. Hanson, G.C. Shurson and P.E. Urriola. 2017. Peroxidized lipids reduce growth performance of poultry and swine: A meta-analysis. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 231:47-58.

Kerr, B.J., W.A. Dozier III and G.C. Shurson. 2016. Lipid digestibility and energy content of distillers’ corn oil in swine and poultry. J. Anim. Sci. 94:2900-2908.

Kerr, B.J., T.A. Kellner and G.C. Shurson. 2015. Characteristics of lipids and their feeding value in swine diets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 6:30.

Lindblom, S.C., W.A. Dozier III, G.C. Shurson and B.J. Kerr. 2017. Digestibility of energy and lipids and oxidative stress in nursery pigs fed commercially available lipids. J. Anim. Sci. 95:239-247.

National Research Council. 2012. Nutrient requirements of swine. 11th rev. ed. Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, D.C.

Shurson, G.C., B.J. Kerr and A.R. Hanson. 2015. Evaluating the quality of feed fats and oils and their effects on pig growth performance. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 6:10.

Song, R., C. Chen, L. Wang, L.J. Johnston, B.J. Kerr, T.E. Weber and G.C. Shurson. 2013. High sulfur content in corn dried distillers grains with solubles protects against oxidized lipids by increasing sulfur-containing antioxidants in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2715-2728.

Wiseman, J., J. Powles and F. Salvador. 1998. Comparison between pigs and poultry in the prediction of dietary energy value of fats. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 71:1-9.

Comments

Post a Comment